by Amy Blakely

Professor Deborah Reed has spent most of her career teaching youngsters to read—and helping teachers improve reading education.

Her interest in the field stems from two very different experiences: studying Russian with dreams of becoming a foreign diplomat and teaching English at an adjudicated alternative school.

After a nationwide search, Reed was hired in July 2022 to direct the College of Education, Health, and Human Sciences’ new Tennessee Reading Research Center: A Reading 360 Initiative. Developed in collaboration with the Tennessee Department of Education and the UT System, the center is a key component of Reading 360, an array of statewide initiatives to ensure that Tennessee school districts, teachers, and families have the resources needed to help students read on grade level by third grade. Reading 360 is a $100 million effort, funded with $60 million of one-time federal COVID-19 relief funding and $40 million in federal grants.

The center has received $5 million over three years through Reading 360 to evaluate Tennessee’s efforts to boost literacy rates by improving teacher training and teacher preparation statewide.

SPARKING A PASSION FOR LITERACY

When Reed was an undergraduate at Claremont McKenna College in California in the early 1990s, the Soviet Union was still intact. She thought learning Russian would be a springboard for a career in international relations.

But mastering Russian was difficult. It meant getting accustomed to a new alphabet, learning to write the Cyrillic letters in print and cursive, and pronouncing some completely foreign sounds.

Reed says she remembers very little about learning English as a child, but “as a young adult studying Russian, I was very aware of learning to read and write a language.”

While in college, Reed taught English to Russian immigrant families and later worked at a nongovernmental organization in Washington, DC. When the Soviet Union broke apart and lost some of its political footing, Reed started looking at other career paths.

She returned to California, got her teaching certificate, and worked at an alternative school for kids expelled from their regular schools. Their attendance was court-ordered.

Expecting to teach middle- and high-school English lessons, Reed quickly discovered her students weren’t ready and that many of them didn’t know how to read very well.

That experience sparked her passion for reading education and working with students from diverse backgrounds who had serious reading challenges. She went on to earn her master’s degree from the University of Texas at San Antonio and her doctorate from UT Austin.

Before coming to UT, Reed helped start the Iowa Reading Research Center at the University of Iowa and served as its director beginning in 2015. There she and her staff designed and conducted more than 20 literacy studies and technical assistance projects. Reed’s research has been funded by state agencies, private foundations, and the Institute of Education Sciences and published in journals including Exceptional Children, Journal of School Psychology, Reading Research Quarterly, Review of Educational Research, and Scientific Studies of Reading.

Like many game-changing endeavors, the center started with a conversation.

“Former Commissioner (of Education Penny Schwinn) reached out to me last year to share her idea for a place where early literacy research could continue for long after her term,” UT System President Randy Boyd says. “She felt that UT, with its reach all across the state, was the obvious partner.”

CEHHS Dean Ellen McIntyre and Professor Sherry Bell, director of literacy initiatives, were enlisted to turn that idea into reality. McIntyre says the college’s literacy experts “are leading the state of Tennessee in expert practices and design of research studies that will make an impact.”

And Bell says UT does indeed have the bandwidth: “With UT’s presence in all 95 counties in Tennessee, the center will be instrumental in communicating and fostering effective literacy practices to positively impact literacy proficiency across our state.”

Hiring Reed meant they’d be able to hit the ground running. “Dr. Reed is an impressive and prolific literacy scholar with a deep understanding of literacy development, acquisition, and effective instructional practices who also has extensive expertise directing other nationally known and regarded reading research centers,” Bell says.

McIntyre agrees: “She understands both literacy instruction and high-quality research study design in ways that will help our state make the best policy decisions based on scientific evidence.”

UNPARALLELED COURSE

There’s much work to be done. Only 36.4 percent of Tennessee students are reading at the “proficient” level, according to the most recent TCAP scores. National tests show Tennessee in the bottom half of states ranked by percentage of students who are reading proficiently.

“The state acknowledges these reading proficiency rates are not acceptable,” Reed says.

She says Reading 360 aims to improve literacy holistically, looking at ways to help students, parents, community groups, educators, and teacher training programs.

One of the center’s key missions will be evaluating teacher participation in professional development and efforts to improve teacher prep programs.

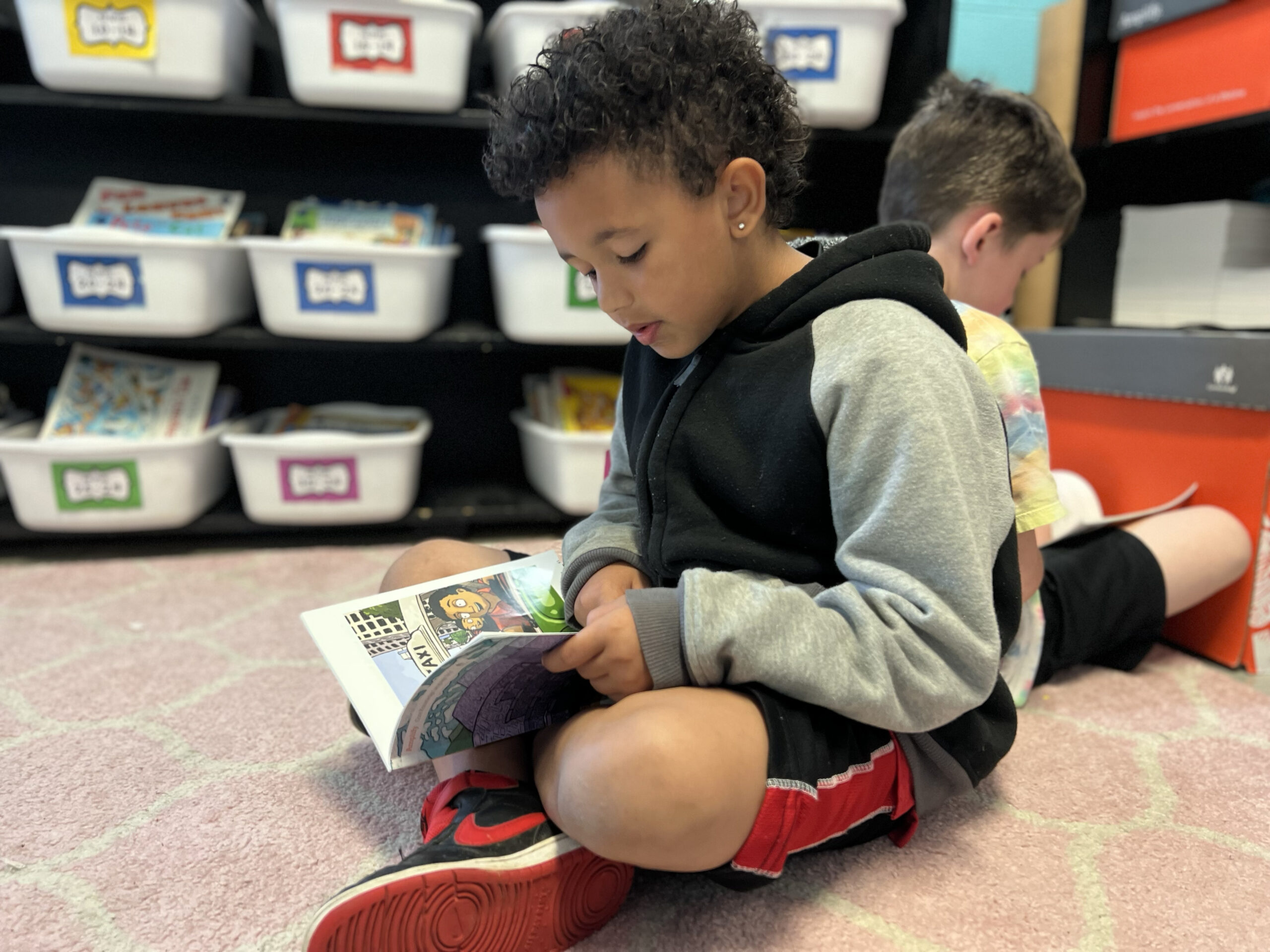

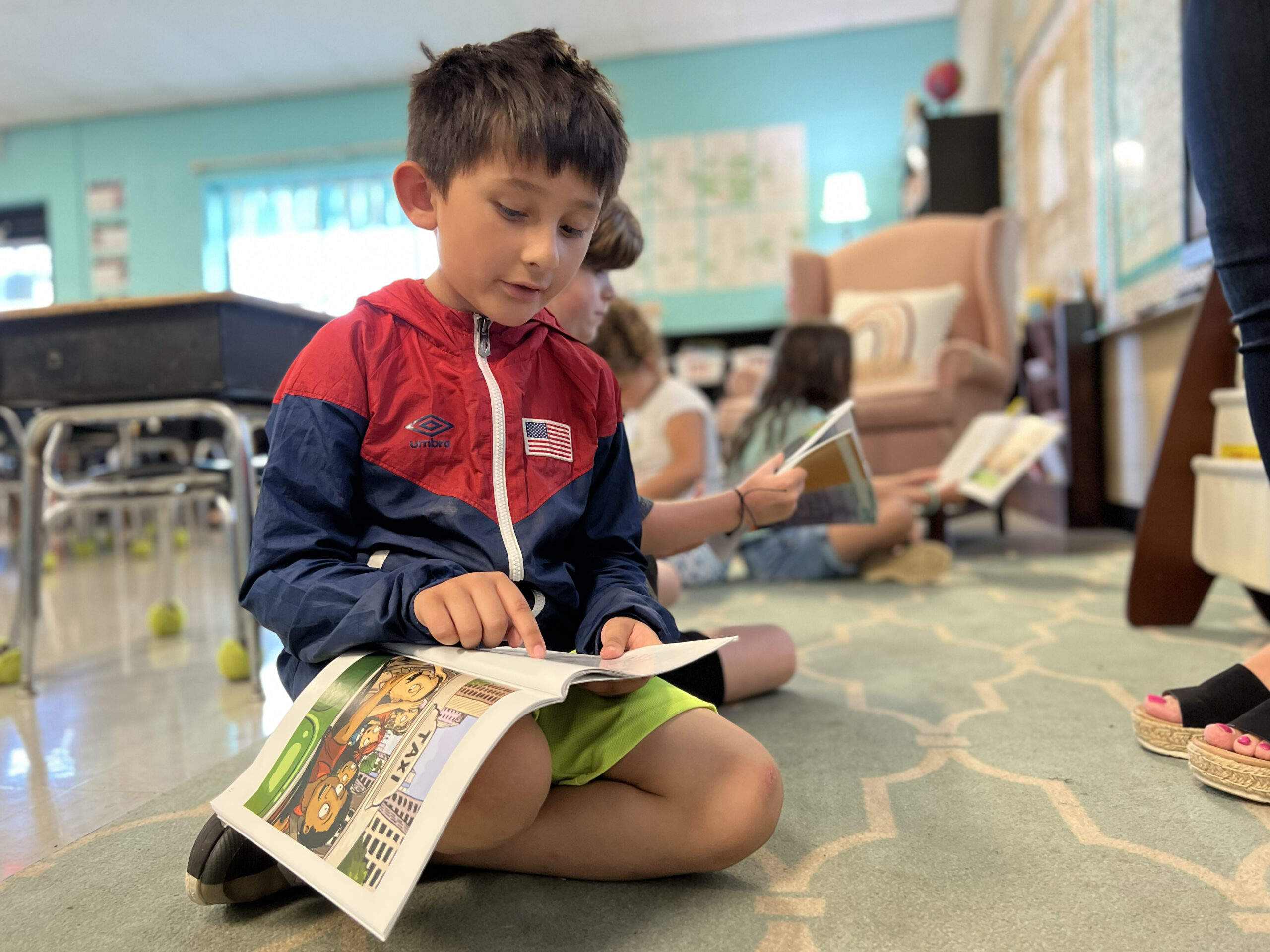

“There is overwhelming evidence about approaches that are most effective in helping all children learn to read,” Reed says. “But schools’ uptake of research has not always kept pace with what we know. The State of Tennessee is making sure that all educators are familiar with the research about reading development and effective literacy instruction and that they’re equipped to implement that in their classrooms.”

Reed says the foundations of literacy are oral language development, phonological awareness (recognizing speech sounds), phonics (linking sounds to letters), and fluency. Tennessee also

stresses vocabulary and comprehension. As part of Reading 360, schools must periodically test reading proficiency prior to third grade so intervention, if needed, can be immediate.

“The early years are so crucial for setting students up for success,” Reed says. Research shows that 75 percent of students who are not reading well by the end of third grade will continue to struggle.

Reed is confident the center will help reverse the state’s lag in literacy.

“The work that Dean McIntyre, Dr. Bell, and the literacy faculty have done set the course for literacy research and the preparation of literacy teachers is unparalleled,” Reed says. “This is the fourth institution where I have been on faculty, and I have never seen a place that so clearly identifies its focus in literacy.”

The center will engage faculty university-wide. Its work will continue long after the state initiative is completed. “This is the starting point,” Reed says. “Everyone is looking to the future of what the center can become and what we might do.”

Reading with Reed

Favorite childhood book:

DR: I read every Little House on the Prairie book when I was young.

What she’s reading now:

DR: I am just starting Remember Me by Mario Escobar and translated by Nashville resident Gretchen Abernathy.

Favorite author:

DR: This is a little like naming your favorite child—or pet, in my case. I cannot pick just one, but I can tell you a few whose craft I greatly admire (in alphabetical order to avoid implying any ranking): Fredrik Backman, Ernest Gaines, John Irving, Liane Moriarty, Jodi Picoult, and Sofia Segovia.

Favorite genre:

DR: Fictional dramas, including literary and historical fiction

Book, audiobook, reading app?

DR: My preference is hard copy, but when I am traveling, I use an app on my phone.

How parents can help their kids become better readers:

DR: Model reading at home and everywhere you go. If you do not like books, read other things such as recipes, instruction manuals, silly stories and jokes, top 10 lists, and advertisements. Make it clear that reading is a part of your life rather than something you have to do. Point out and comment on features like unique words and phrases, different punctuation marks, short vs long sentences, and even the way the letters ‘a’ or ‘g’ appear in different fonts. Ask questions while reading the book or other material to help children think about the ideas, understand the events or information, and relate the reading to everyday life.