By Whitney Heins

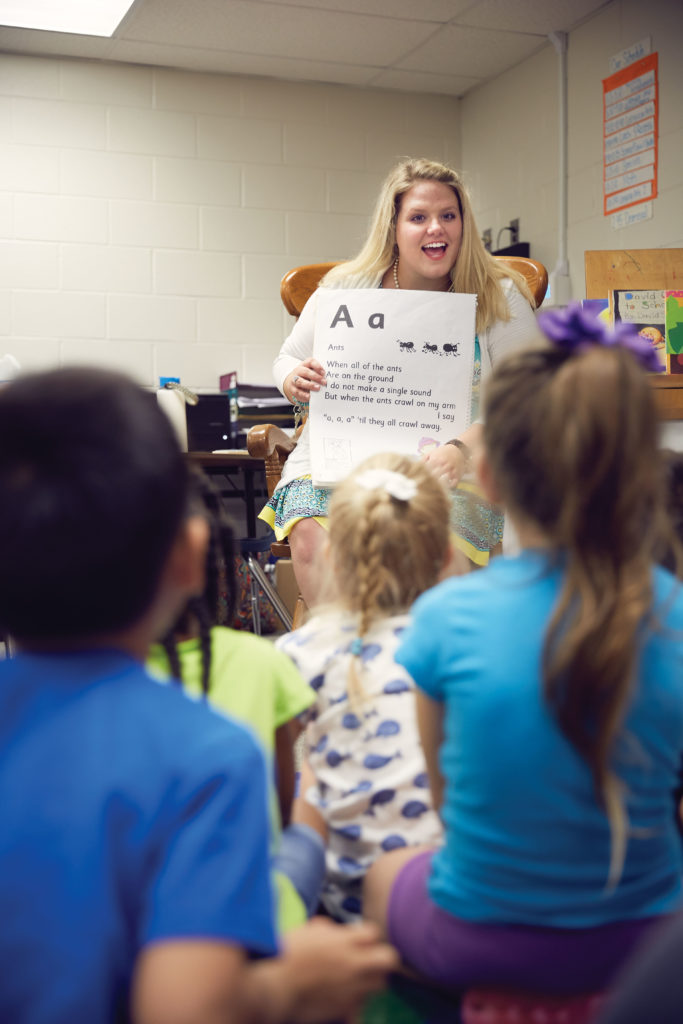

When Katie Potter (’16) was a girl, she hardly went anywhere without her workbooks, teaching charts, and grade books. Even on car trips, they’d be in tow.

Potter didn’t need these materials for school. She needed them to prepare for living her dream.

“My whole life, all I’ve ever known was that I wanted to be a teacher. I’d play teacher all the time. And when my mom and dad couldn’t play with me, I’d just pretend they were getting the answers wrong,” laughed the recent graduate of the college’s five-year teacher licensure program.

Some of the car rides were with her dad from her hometown in South Carolina to Big Orange country, where she’d revel in watching the Vols play. So it only made sense that when it came time to pursue her dream, she’d be going to her dream school—the University of Tennessee.

“I put all of my eggs in one basket. I only ever wanted to be a teacher and I only ever wanted to go to UT. It was the only school I applied to.”

While Potter was growing up, UT’s five-year teacher licensure program was growing up, too. Implemented in 1990, the program was cutting edge if not controversial.

It was born from a national education reform movement away from undergraduate degrees in education and toward degrees in the content area students wanted to teach—coupled with a minor in education and an internship.

“The learning theory was to avoid front-loading content and instead combine coursework, reflection, and thoughtful consideration of what it means to be an effective teacher,” explains Susan Benner, associate dean and director of the Graduate School of Education. “The material that the students would be learning would run concurrently with their opportunity to be a teacher.”

UT worked with about a hundred other academic institutions to conceptualize the model but was one of the few to actually implement it.

And it wasn’t easy.

The multiyear journey began with a mountain retreat by the entire college faculty to hammer out the pros and cons of the program, which would ultimately combine a master’s degree with a yearlong internship.

The pros were that within five years, students would have earned an undergraduate degree, a master’s degree, and a year of experience recognized by the state. The yearlong internship was especially radical since most schools then—and even today—require only six months or less of student-teaching.

“We really wanted the yearlong model because something different is happening throughout the entire school year,” remembered Benner, who played a key role in the program’s implementation. “For example, if a (university) student starts in (an elementary or secondary grade) classroom where school has been in session for a few weeks, they miss how to launch the curriculum and engage with students.”

The program’s cons were that students would have to attend and pay for another year of school, be on an academic school calendar different from the university’s, and apply to a much more selective program. In addition to a more competitive GPA requirement, candidates would need to go through several personal interviews to be considered. No longer would education be a student’s fallback plan.

“Some people thought it was the worst idea ever and that this model would scare away students,” says Benner.

But the opposite happened. Student interest and attention increased. In fact, there is enough interest today to triple enrollment.

Financial gifts such as the one from David Bailey—who was inspired by another donor, J. Clayton Arnold—have also helped attract interest. Bailey’s gifts alone have positively impacted more than 500 students, who have then gone on to positively impact the lives of the students they teach.

“The gifts provided by David Bailey and J. Clayton Arnold have made the difference in whether or not these students could complete our five-year program or not,” says Dean Bob Rider. “I personally don’t think we would still be offering this program without the generosity of these two individuals.”

“Generous donors like these allow us to work with students so that the economic strain of the program does not prevent them from being teachers,” added Benner.

For Potter, the internship was the clincher. It allowed her to not only learn about teaching but also apply what she was learning in a real-world setting.

“I’ve talked with so many principals and teachers who are amazed and impressed by the yearlong internship,” she says. “I know so much more than if I had just spent a few months in a school.”

Still, the days were grueling. Potter says she was a full-time teacher as well as a full-time student. She taught Mondays through Thursdays, leading after-school activities a couple days a week. On Fridays, she was back to being a student again. And somewhere in between she had to find time to complete her coursework. Despite the difficult schedule, Potter never doubted the program’s worth.

“Seeing a lightbulb go on in a child after struggling with a subject is so immensely rewarding,” she shared.

The metamorphosis Potter has seen in her students is not unlike what Benner has witnessed in her own.

“We see these students go from being university students that think they want to be teachers to being professional teachers. It is great fun to watch,” Benner says.

In fact, about 80 percent of the program’s students who want to be teachers (instead of pursuing things like a doctoral degree) get jobs.

Like the students, the five-year teacher licensure program is constantly changing and growing. The curriculum responds to workforce needs to ensure it produces teachers that will make a profound societal impact.

“Being a teacher is far more complicated than showing up on time and running kids through programming. It’s about relationships, building motivation, and having a deep commitment to children and the communities they come from,” says Benner. “I’m very proud of our program and our graduates that we send out who are ready to lead their own classrooms.”

Potter began living her dream as a real kindergarten teacher this fall at Sugar Hill Elementary school in North Georgia.

“I am that girl who never grew out of wanting to be a teacher—and now I get to be one,” she says. “And my parents are happy that I finally have real students to teach.”

Photography by Gregory Miller